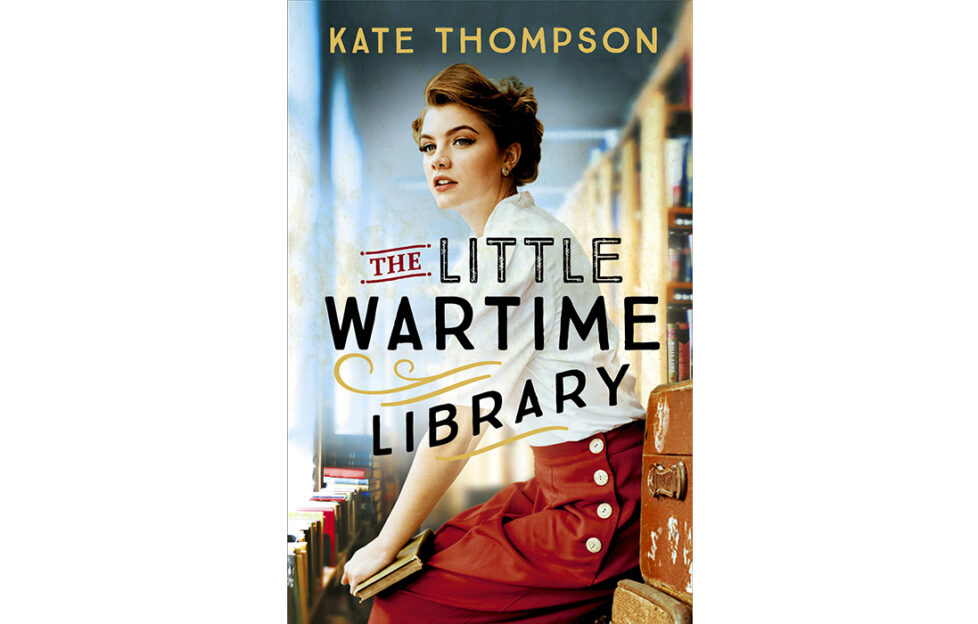

Q & A With Author Kate Thompson

Kate Thompson, author of The Little Wartime Library, shares stories from the fascinating real-life inspiration behind her book, stories from the brilliant women she’s met through her research and even drops a few hints about the book she’s working on now! You’ll find a short story by Kate inside this week’s issue of My Weekly – pick it up now!

Tell us a bit about your latest book and what inspired you to write it…

At the start of World War II, Winston Churchill warned: ‘We must expect many unpleasant surprises.’ And there is little doubt that over the next six brutal years of war, the people of London’s Bethnal Green had more than their fair share of unspeakable deprivation, sacrifice and bloodshed. Yet there is one story to unfold from this tight-knit East End community that reveals even during the horror of warfare, occasionally – just occasionally – there can be a little magic too…

The story begins on 7th September, 1940, when a bomb crashed through the roof of Bethnal Green Central library at 5.55pm on what would later be known as ‘Black Saturday’, the start of the Blitz. What had been an orderly and well-equipped library became, in a split second, a scene of destruction. And yet, rather than simply hurrying for the nearest shelter, the borough librarian, George F. Vale and his deputy, Stanley Snaith, calmly pulled a tarpaulin over the shattered glass dome roof and set about planning a pioneering social experiment that would transform the lives of wartime Londoners. This was to become known as Bethnal Green’s secret Underground wartime library. It gave working-class East Enders access to books and most importantly, gave them the chance to escape the realities of war as they lost themselves in the pages of fiction, of romance and history.

Bethnal Green Underground was a half-completed stop on the Central Line when war broke out. Builders were working on connecting it to Liverpool Street, but from September 1939 it had been locked up and left to the rats. One week after the Blitz began, East Enders defied Churchill’s orders not to shelter in Tube stations and claimed their right to safety. At 78 feet below ground, it was one of the few really safe places to shelter in Bethnal Green.

Three months after the Blitz began, in December 1940, Bethnal Green Borough Council leased the station from the London Passenger Transport Board for £510 per annum and the station was transformed into a fully functioning community with an astonishingly advanced array of facilities. Metal triple bunks, sleeping up to 5,000 stretched three-quarters of a mile up the eastbound tunnel. A shelter ticket reserved you a bunk and you needed it. On one fiery Blitz night, a record 7,000 people slept down there. Order was kept by a stout, no-nonsense ARP warden by the name of Mrs Chumbley, who reputedly ruled with a rod of iron. Her booming voice could be heard echoing up the tunnels.

Shelterers weren’t short of entertainment. There was a 300-seat theatre with a stage, spotlights and a grand piano, which hosted opera, ballet and wartime weddings, a café serving hot pies and bacon sandwiches, doctor’s quarters and a W.V.S staffed wartime nursery, which enabled newly enfranchised women to go out to work. And best of all, from October 1941, built over the boarded-up tracks of the westbound tunnel – a little library!

The library, which had a captive audience during a raid when the doors to the shelter were locked, was open from 5.30pm to 8pm every evening and loaned out 4,000 volumes of consciously chosen stock. Romance sat alongside literary classics, children’s books, poetry and plays. Treasure Island, Secret Garden and many other classics, including Enid Blyton, nourished young minds and helped children to escape the unfolding nightmares above.

I discovered the library quite by chance from one of its former users, Pat Spicer.

“It was a sanctuary to me,” Pat, now 92, told me. “By 1943, I was 14 and there had been so much horror, the Blitz, the Tube disaster. You can’t imagine what that library represented to me as a place of safety. It sparked a life-long love of reading.”

That last sentence sparked the whole idea for The Little Wartime Library!

London’s East End is like a character in its own right in your books – what draws you to that particular setting?

I love the East End and East Enders. The women are thrifty, irreverent, crafty, subversive, born survivors, or as one woman said to me in describing her wartime nan. “She was a warrior in a wrap-over apron.” But most importantly, they value kindness above all.

Can you tell us a bit about the research you undertook for your latest book, The Little Wartime Library? What was your most surprising/interesting discovery?

I studied a 1942 Mass Observation Survey entitled ‘Books and the Public’ which offered up a fascinating insight into the reading habits of the beleaguered wartime public.

The Mass Observation Surveys are fascinating, because they offer a snapshot into working class culture and feature the innermost thoughts of women whose voices would ordinarily be lost to history.

But the success of the public municipal library is the untold story here. Libraries boomed in wartime as book sales dipped. Four out of ten people borrowed books from a library in wartime and it transformed lives. And best of all, unlike a Boots subscription library or a tuppenny library, it was free.

The survey found that many people, especially young working-class women, developed a passion for reading that their parents never had the time for and joined the library for the first time. Some began reading during the Blitz to keep their minds off the bombs and kept it up. Twice as many women as men used the library and they preferred fiction.

Fiction readers typically devoured their books in just four days, while non-fiction readers took three times as long. In moments of severe conflict like the evacuation of Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain, the Blitz and then the V1 and V2 rocket attacks, women gravitated to romance, historical fiction and thrillers for escape.

With the war seemingly unrelenting, women wanted escapism with a strong conquering heroine. This would explain the success of the first ever bodice ripper. It wasn’t published in the United Kingdom until shortly after the war, but when Forever Amber by Kathleen Winsor came out in America in 1944, it was a publishing sensation.

Set in the 17th century during the bubonic plague and the Great Fire of London, its heroine Amber ruthlessly uses her sexuality to scheme and manipulate her way through Restoration London.

The chapters set during the plague are absolutely riveting, especially when you find yourself reading it mid-lockdown during another global pandemic. The sound of the dead cart rattling over the cobblestones and the chiming of the bell, entreating people to, “Bring out your dead,” makes for chilling, but page-turning reading. And it made me think. Did women reading about pox and fire in the 17th century, in the ruins of a post-war 20th century landscape, draw reassurance from its pages?

Is that why historical fiction was so popular during WW2? Our small island had survived wars, fire, threat of invasion and disease before. And so too this shall pass?

You must have spoken to so many inspiring and interesting women while researching your books – tell me about one who particularly stands out in your memory?

Beatty Orwell is an incredible woman who I count myself lucky to have as a friend. Beatty is 104 and was born when London was under attack from German aircraft during WW1! Beatty was born to a tough Jewish lady who worked all the hours to feed Beatty and her sister after the death of their father. She fought fascism and the blackshirts at the Battle of Cable Street, made munitions during WW2 and after the war ended, became the first lady mayoress of Bethnal Green, to help fight for better housing and care of the elderly. She’s a walking, talking piece of history. She taught me it’s important to stand up for what you believe in and live collectively, not individually.

If you could travel in a time machine back to the 1940s, where would you visit? What would you do? Who would you want to meet?

Beatty Orwell! I know her today as an elderly, formidable woman. I’d love to meet the younger version too!

You’re a big supporter of libraries which can obviously enrich lives in so many ways. Tell me about some of your favourite times spent in a library…

As a child, in the 1970s and ’80s, I loved visiting my local library. Coming from a noisy household, I embraced the feeling of solitude and order. As soon as I caught the intoxicating scent of old paper and polish and heard that satisfying thunk of the librarian’s stamp, I relaxed. It was no red brick, or arts and crafts architectural beauty, more of a concrete civic centre box, with scratchy grey carpets and spider plants behind the desk, but that didn’t matter. It was a destination and I can still vividly remember the feeling of calm and freedom that came over me as I walked through the door. It was my haven.

First came the ritual of choosing the book, then I’d take it to the furthest end of the library, rather like a dog scurries off with a juicy bone, sit on a small green plastic chair and fall into a story, while my mum stood at the counter and gossiped (in a theatrical whisper) with smiley Jacky the librarian, who always let her off the late fines. I vividly remember thinking as a small child, how interesting, so rules can be broken!

Like most, when it came to Enid Blyton I virtually read the print off the page. Malory Towers gave me the keys to a boarding school experience I’d never have. Black Beauty the opportunity to own the horse I so desperately wanted, The Secret Garden the delicious possibility of finding undiscovered doors.

It unlocked my imagination in a way that always made me feel safe. Without weekly trips to my local library, I’m fairly certain I wouldn’t be a writer today and I’m forever grateful to my mum for taking me.

Are you working on a new book? Any hints as to what it’s going to be about?

If I told you I’m travelling to Jersey soon and I’m fascinated by the Occupation of the Channel Islands that would be a big hint!

What do you enjoy doing when you’re not busy writing?

Walking my beautiful rescue Lurcher, Ted, cooking (and eating) and as much as I moan about it, running around after my two boys!

How and when did you get started as a writer and what tips would you give to aspiring authors?

I was, and still am, a journalist and that taught me that everyone has a story, and true life is always more interesting than anything you can make up. Write, as author Stephen King describes in his memoir, as if the door is shut – in other words, no one will read it. Then you can really have fun with it, indulge your creativity and most importantly, just lose yourself in your make believe world of characters.

What book have you read recently and enjoyed?

I read All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, about a blind girl in Occupied France and it felt so astonishingly real to me. I can’t stop thinking about it. His writing is beyond beautiful.

The Little Wartime Library by Kate Thompson, published by Hodder & Stoughton is out now in hardback and available from Amazon. Paperback release, September 2022. Don’t forget to pick up a copy of this week’s My Weekly to find an exclusive story from Kate based on her latest book.

Connect with Kate:

Facebook @KateThompsonAuthor

Instagram @katethompsonauthor

Twitter @katethompson380